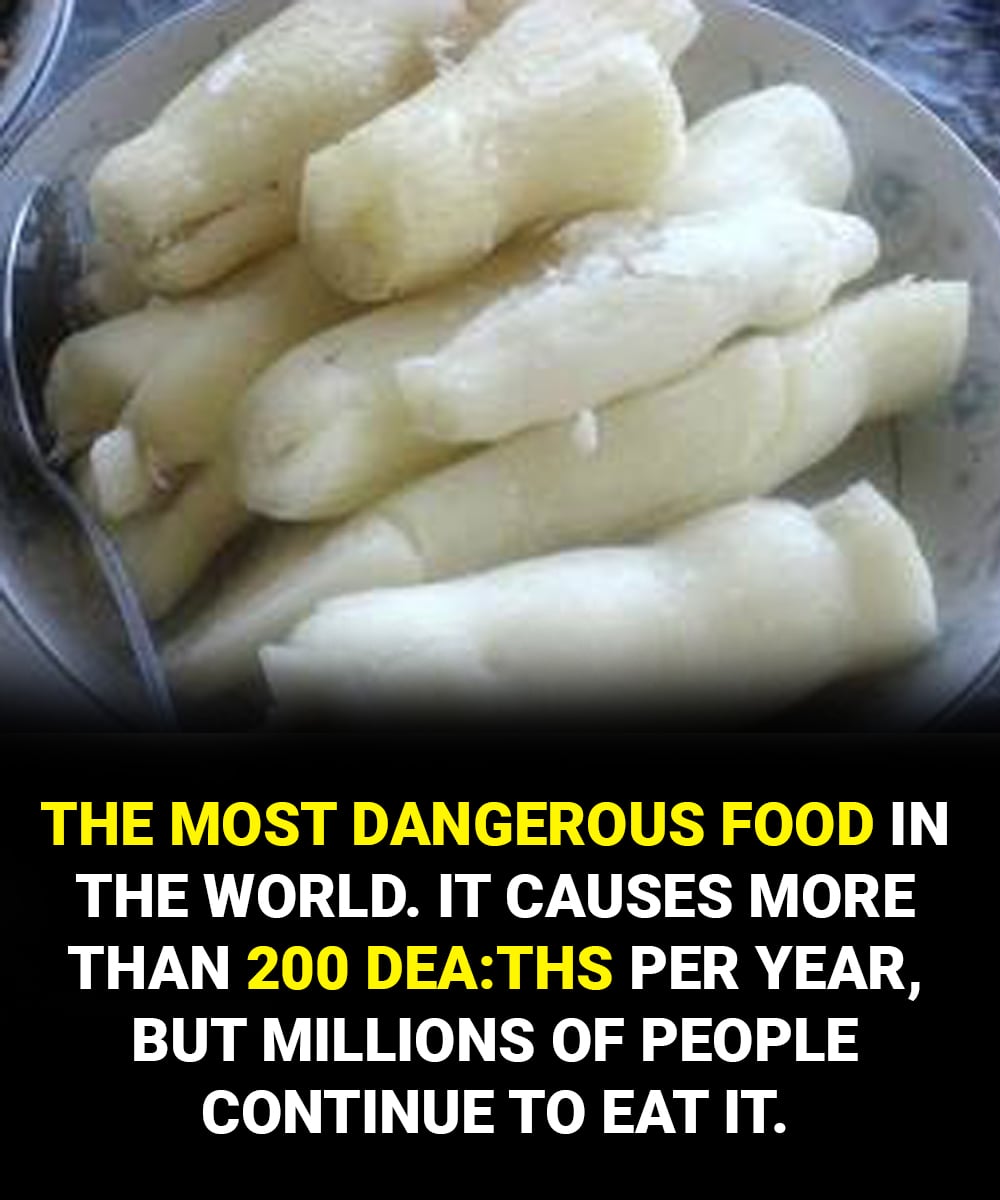

Cassava is a beloved ingredient across continents, from South America to Southeast Asia, but few realize that the root can release cyanide if not properly processed. The issue lies mainly in the “bitter” varieties, which contain higher levels of cyanogenic glycosides. When the root is cut, grated, or chewed, natural enzymes trigger the formation of cyanide — the same toxin infamous in crime novels.

Improper preparation has caused poisoning outbreaks in vulnerable regions and even contributed to konzo, a neurological condition seen in parts of Africa. In communities facing drought, food shortages, or lack of fuel for cooking, cassava is sometimes consumed without the traditional steps needed to make it safe. Repeated intake of inadequately processed cassava can damage the nervous system, leading to sudden, irreversible weakness in the legs.

Fortunately, cassava becomes perfectly safe with simple techniques used for generations.

-

Peel deeply: The outer layers hold most of the toxins.

-

Soak or ferment: Grating or peeling the root and leaving it in water for 24–48 hours helps reduce cyanide levels.

-

Boil thoroughly: Cooking for at least 20 minutes neutralizes the harmful compounds.

-

Pair with protein: Foods like eggs, fish, or beans help the body process small traces of cyanide.

When these steps are followed, cassava transforms from a potential hazard into a nourishing, gluten-free source of energy. It can be turned into soft cakes, crispy fries, breads, porridges, and the beloved farinha d’água of Northern Brazil.

In the end, cassava isn’t the villain.

As one might say, “It is knowledge—not fear—that keeps a traditional food both safe and delicious.”

With the right preparation, this versatile root remains a vital, flavorful part of diets worldwide.